MY

RESEARCH

The primary goals of my research are to understand what psychological factors drive behavioural adaptability in animals and how this influences public attitudes and behaviour towards those species. Collectively, my work is important for understanding the past, present, and future of human-wildlife coexistence in an ever-changing world.

WHAT’S “PSYCHOLOGICAL” ABOUT BEHAVIOURAL ADAPTABILITY?

Some animals are very good at adapting to their environment, while other species are not and ultimately go extinct.

Scientists do not yet fully understand whether species differences in behavioural adaptability are underpinned by one or more psychological abilities or, indeed, something else entirely (e.g., opportunities or need for behavioural change). Over the years, my team has worked with a wide variety of species to find out.

Much of my earlier work on animal psychology focused on non-human primates, particularly monkeys and apes. My fascination with these animals stemmed from the obvious fact that they are incredibly adaptable animals, and because I had already spent several years working with them in the wild. Later on, I began to realise that most of what humans know about animal psychology stems from a very limited set of animals (e.g., primates, rodents, and birds). I therefore redirected my focus to explore other branches of the animal kingdom, which has led to my current work on wild carnivores.

Through my combined training in zoology and psychology, I have studied a wide range of psychological processes related to behavioural adaptability in animals, including for example:

• Boldness – FIND OUT MORE

• Problem-solving – FIND OUT MORE

• Associative Learning – FIND OUT MORE

• Personality Structure – FIND OUT MORE

• Social Perception – FIND OUT MORE

• Exploration and Spontaneous Tool Use – FIND OUT MORE

• Motivational Traits – FIND OUT MORE

HUMAN’S CONNECTION WITH NATURE

Along with studying animal psychology, another important part of my work relates to understanding how such research impacts public attitudes and beliefs about wildlife.

Most global environmental problems hinge on people developing a stronger sense of empathy and stewardship for protecting the natural world. Humans have a long history of separating themselves from other species. Up to around Victorian times, for example, there was very little acknowledgement or regard for animals being anything more than machines guided by instinct rather than flexible decision-making derived from their own conscious thoughts.

The notion that animals have personality, for example, has traditionally received much resistance from scientists because it was viewed as being too anthropomorphic to be an objective field of science. Even today, you can go to a scientific conference and talk about animal personality and still find some scientists challenging the notion. Researchers have gone from calling it different names (e.g., dispositions, temperaments, syndromes) to putting the word in quotation marks (“personality”). But while it is indeed important to always be vigilant against anthropomorphism, it is equally important not to be “anthropo-phobic”, and one of the biggest curiosities, despite many scientists’ resistance, is the fact that they themselves can accurately gauge the personalities of other species when you ask them! This latter point can be illustrated by two examples from my own research:

In 2013, my colleagues and I gave questionnaires to people who had been working with monkeys for over a year, to test whether they could reliably rate the personalities of those monkeys. The questionnaire asked the people to rate on a scale from 1 to 7 how much certain behaviours were expressed by each monkey. To determine whether the questionnaire responses were valid, we quantified behavioural observations on the same monkeys to see whether individual differences in monkeys’ behaviour reflected the raters’ scores from the survey. We found that both measures reflected each other, demonstrating that the raters gave an accurate portrayal of monkeys’ personalities (SEE HERE). Similarly, in 2020, we assessed whether human raters could reliably rate monkeys for levels of innovative behavior and motivation. We found that rated innovation predicted performance on a learning task, and rated motivation predicted participation in the task (SEE HERE).

Collectively, what these and other studies suggest is that, in at least some respects, humans do indeed have the capacity to accurately perceive psychological traits in other species. Such abilities may be a key factor in helping our society restore its sense of empathy and connection to the natural world.

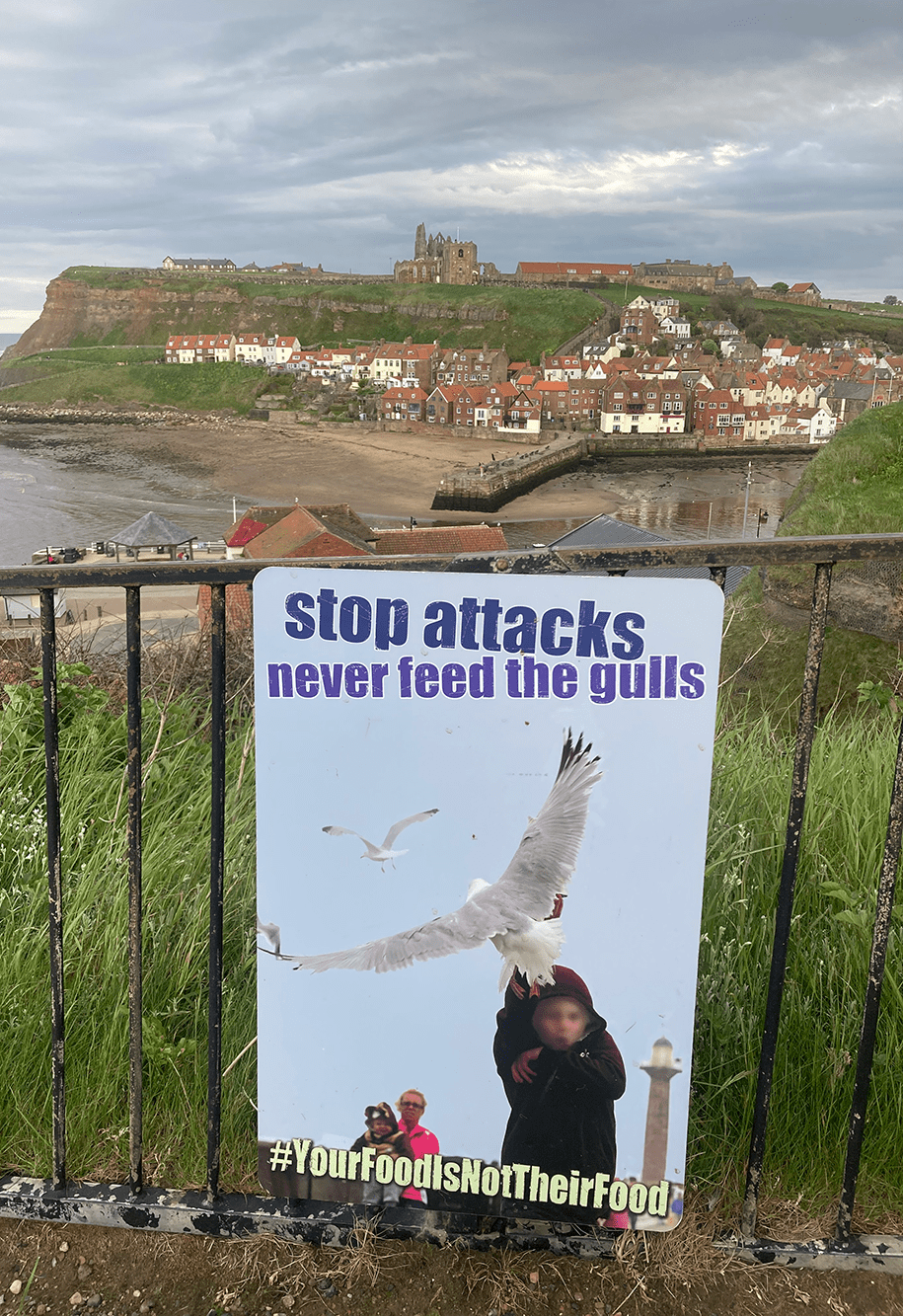

But, importantly, how does greater awareness of animal psychology change people’s views and connection with wildlife? Research on the psychological abilities of animals indeed receives major global media attention, and educational talks on the intelligence and personality of animals can, in some cases, encourage people to learn about and support their welfare and conservation. However, educating people about animal psychology could have limited impact because, for example, many species are often regarded as dangerous or pests to society. Thus, getting local communities to support the conservation and general well-being of these animals can be difficult because it comes at a perceived cost.

Thus, to better understand the relationships between animal psychology, human-wildlife conflict, and people’s willingness to tolerate and support local wildlife, I established two research programmes in 2018 and 2021, respectively, focusing on wild free-ranging carnivores due to their incredible behavioural adaptability and highly polarised reputation in human society. If you’d like to learn more about both of these programmes, check out the CASE STUDIES page!

FIELD SITES

One of the joys of studying animals is that they are everywhere!

My work has taken me all over the world, from the tropical rainforests of Central Africa and Brazil, to the dramatic landscapes of Scotland and England. Such extensive travel has greatly facilitated my experience and understanding of animal behavioural adaptability in different environments, as well as my appreciation for differences in public attitudes and perception of wildlife.

To learn more about the places my team and I go to, check out the MEDIA section here!

METHODS FOR RESEARCH

Attributing a specific psychological trait to explain animal behaviour risks overlooking alternative explanations for that behaviour, unless scientists have objective evidence for the trait’s existence.

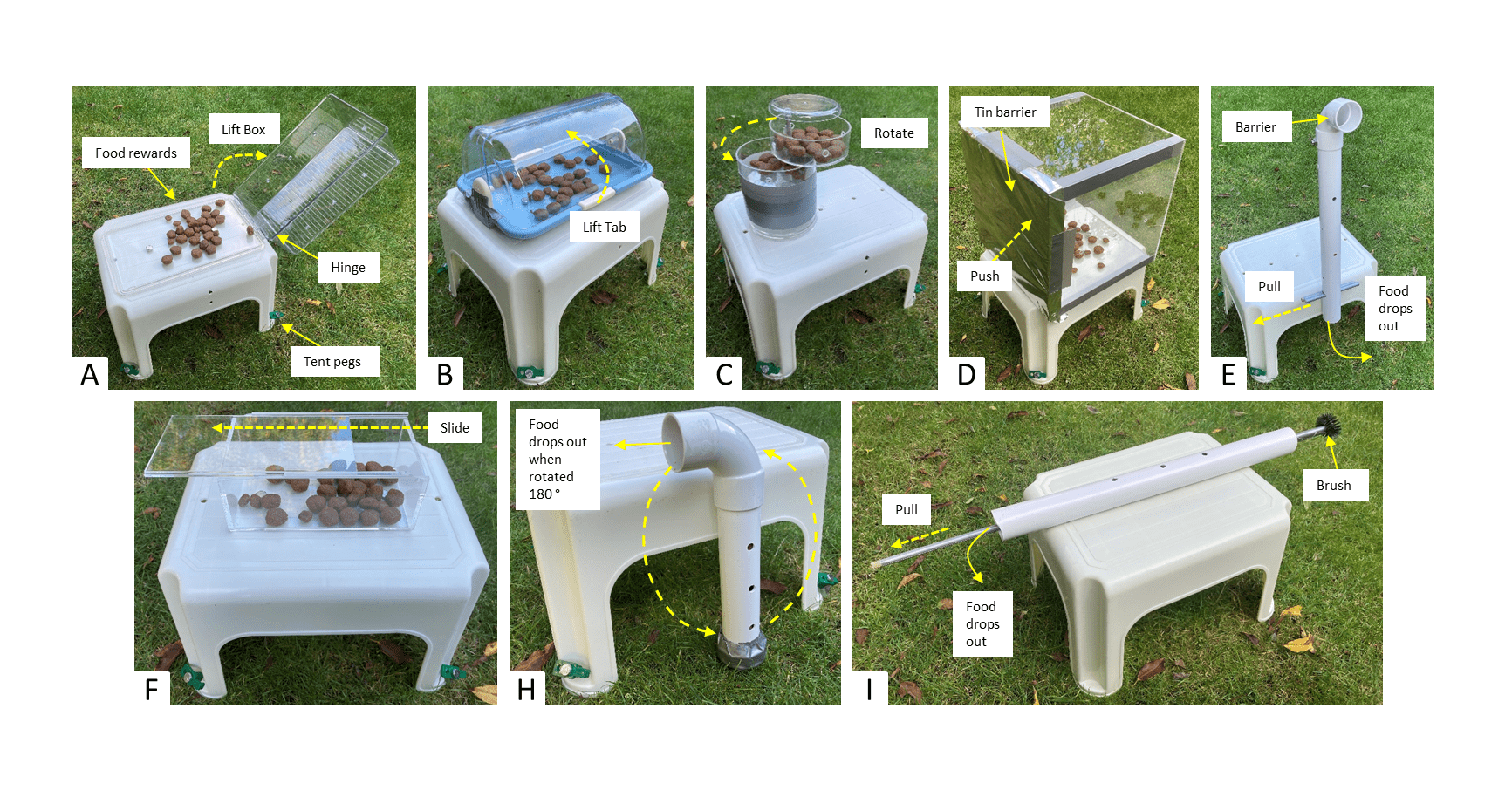

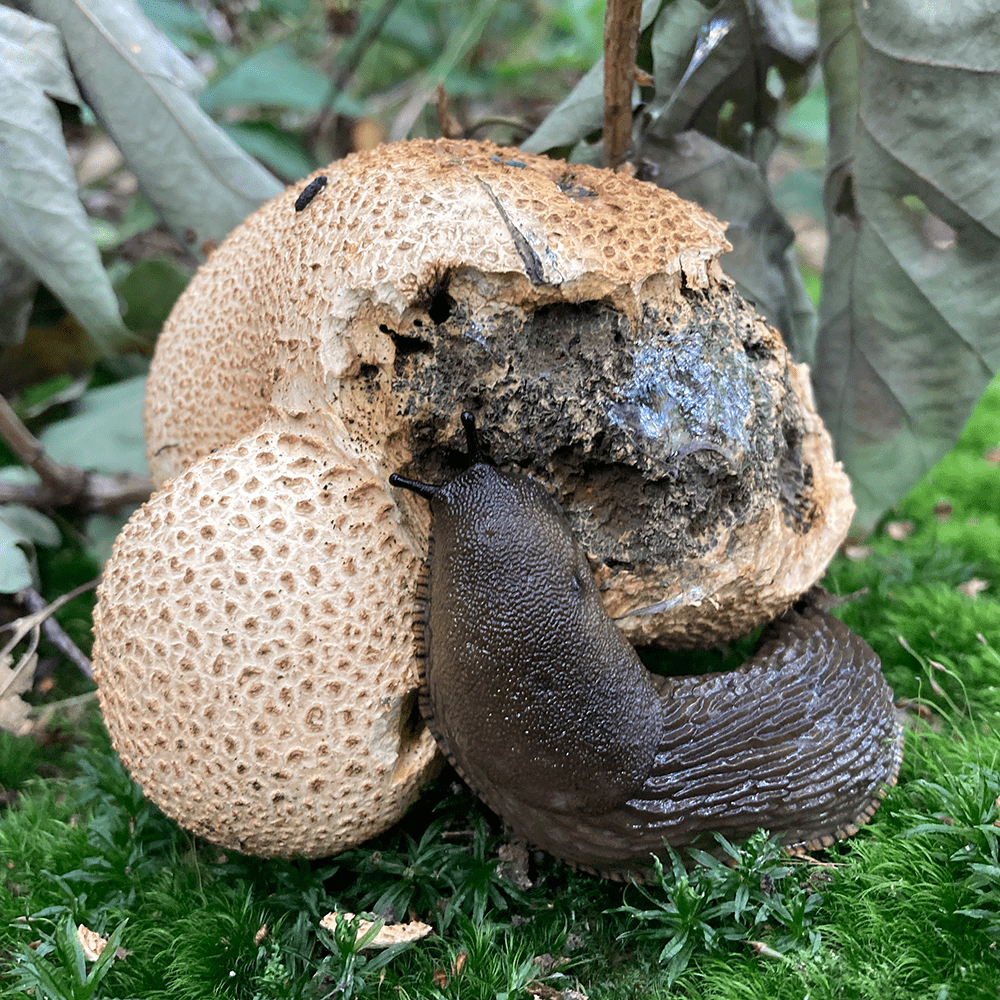

Animals’ minds are like black boxes – we cannot see directly inside their heads to know what they are thinking. Consider, for instance, your own observations of people: if you observe someone smiling, how do you know they’re actually happy versus pretending ? Thus, given the difficulty of being able to interpret the emotional and cognitive underpinnings of behaviour, my team and I use a combination of methods to help infer the existence of psychological abilities in animals, much like human psychologists do with their participants. One common approach includes the use of psychometric tests, i.e., tasks designed to measure a specific ability in animals. For instance, the puzzle feeder you see in the photo to your right was designed to test whether wild raccoons naturally possess knowledge on how to use sticks to retrieve an out-of-reach food reward, which several species of primates and birds are famous for doing (called “spontaneous tool use”). However, despite sticks being widely available throughout their habitat and possessing many of the physical, cognitive, and behavioural traits as other tool-using species, raccoons were interested in the food rewards but mostly ignored the sticks, suggesting that other factors are needed for tool use. To read more about this study, SEE HERE.

Ethical Note: My team’s top priority is the safety and well-being of the people and animals we study. None of the work we do is invasive to wildlife; it is entirely observational and on wild free-ranging animals. Part of our extended research network includes several world-leading animal welfare scientists, and our methods are ethically reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare & Ethics Research Board at the University of Hull. Our methods also follow all ethical guidelines set out by the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. Finally, we work very closely with a range of government and scientific officials (e.g., wildlife biologists, park managers, and city council members) who keep us updated on the most recent wildlife policies and legislation.

impact of my work

While NASA and others may turn to the stars to look for signs of intelligent life, such life already exists here on Earth in the many animals sharing the planet with us.

Unfortunately, though, for many of these species, we are letting them go extinct as a consequence of human activities. Thus, an important goal, and therefore legacy, of my work is to help raise knowledge and awareness about animals to foster a deeper sense of appreciation and understanding about the world around us.

The early days of my career in animal psychology started out in Central Africa, where I was working with various conservation groups to habituate wild western lowland gorillas for the purpose of research and ecotourism. To understand how to save a species, we must be able to observe and understand their behaviour, and habituation allowed us to do this. Protecting the health of these animals throughout the habituation process was a top priority, and so I was among the first team of scientists to quantify and publish information about the impact of habituation on the health and reproduction of this highly charismatic species (SEE HERE). This work was cited in the IUCN Best Practice Guidelines for Health Monitoring and Disease Control in Great Ape Populations (SEE HERE) – a global guide to research and tourism involving great apes throughout Asia and Africa.

From 2010 to 2018, the majority of my work focused on developing novel techniques to study animal personality and cognition, particularly in monkeys, but also great apes and bottlenose dolphins. It was during this time that I completed my PhD, which explored the relationship between individual differences in animal learning, personality, and social networks. From this work, I became one of the first scientists to publish data on the personality structure of bottlenose dolphins (SEE HERE) and a New World primate species (SEE HERE), which provided some of the first evidence to support the notion that animal personality traits can evolve through convergent evolution. My work also became one of the first illustrations that personality traits have the potential to shape animals’ social relationships beyond the basic “social rules” often attributed by scientists (SEE HERE). Some of this work was recently highlighted as a case study in Nature for the newly-proposed STRANGE framework because it emphasised the need for taking animal personality into consideration to help reduce sampling bias in animal cognition research (SEE HERE).

Since 2018, I have returned to the field of conservation biology to apply my training in animal psychology to address some of the world’s most pressing environmental issues. This work, conducted primarily with wild mammalian carnivores, has begun to shed unique insight into how carnivores perceive and respond to novel changes to their environment. For instance, despite the popular belief that bold and innovative behaviour helps urban foxes raid litter and outdoor bins, our work has shown that urbanisation throughout Scotland and England does not necessarily encourage all foxes to exploit food-related objects upon discovering them. Instead, how foxes react to environmental changes, including random foraging opportunities, is more nuanced and may involve factors related to how foxes perceive risk, effort, or both. Such findings are important for assessing the impact of human activities (like urbanisation) on wildlife, and may help change negative public attitudes towards foxes, which have a long history of being persecuted as a “pest” by UK residents. To read more about this study, SEE HERE.

In terms of a cultural impact on society, my work has garnered major attention from the world’s media. In 2021, for example, I received news coverage from over 200 global outlets within 48 hours of my work on dolphin personality being published, leading to multiple in-person radio/television interviews and newspaper/magazine coverage being translated into at least seven other languages, including Arabic, Korean, Japanese, Greek, French, Italian, and Spanish (SEE HERE). More recently, my work on wild carnivores has been covered by National Geographic magazine in 2022 (SEE HERE) and was featured on the BAFTA award-winning BBC Winterwatch television series in 2023 (SEE HERE), which was viewed by millions of people. Collectively, these and other examples have been important reminders of the interest people show in animal psychology, and the role that global media plays in helping to generate public awareness and understanding of the many species that share the planet with us.

![Badger_logo_design_vector_template [Converted]](https://www.blakemorton.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Badger_logo_design_vector_template-Converted-1-300x55.png)